A certain Mr Buffett with his folksy wisdom often wraps deep insights into

absurdly simple language. He insists that the first rule of investing is to not lose money. And that the second rule is not to forget rule one. Clearly losing

money is never fun, but we can recover this fairly quickly if the price picks

up, can’t we?

The table below illustrates why Buffett’s words are key:

Loss

|

Gain required to breakeven

|

-10%

|

11%

|

-20%

|

25%

|

-30%

|

43%

|

-40%

|

67%

|

-50%

|

100%

|

-60%

|

150%

|

-70%

|

233%

|

-80%

|

400%

|

-90%

|

900%

|

It shows us that a loss of 10%, needs an 11% uplift to get

back to where we started. No problem. But a 50% loss requires a 100% gain to recover

the loss. Percentages can be a little slippery, so to put it into more

concrete terms:

Starting investment value = £100

10% loss = £10

New investment value = £90

A 10% increase of the new value of £90 only takes us to £99, not the original

£100. For this we need an 11% uplift.

Starting investment value = £100

50% loss = £50

New investment value = £50

A 50% increase of the new value of £50 only gives a return of £25 so only takes us back to £75. To get back to the original £100 we need a 100% increase.

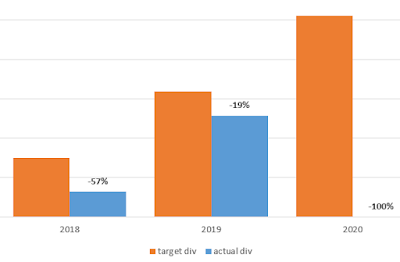

A chart shows these nasty consequences clearly:

We can use the same arithmetic to get another perspective on gains and losses:

Starting investment value = £100

Gain of 100% = £100

New investment value = £200

New investment value = £200

A loss of 50% = £100

Taking the value back to £100

A more dramatic example in my view is the 233% gain in the chart above, which needs only a 70% drop to wipe out all of the gain.

A google sheet is available here with this chart and some sample calculations.

A more dramatic example in my view is the 233% gain in the chart above, which needs only a 70% drop to wipe out all of the gain.

A google sheet is available here with this chart and some sample calculations.

A significant loss recorded against an investment could

therefore take a while to get back into positive territory. But also a

significant gain could be wiped out with what appears to be a much smaller

loss.

Based on the above, losses can have a disproportionate

impact on gains, and a portfolio. And it should be evident that a see-saw of

gains and losses would end up with an investment losing money. The extent to

which this could happen is modelled in the chart below. This shows the result of a successive gains and losses of 10% iterated 100 times.

The values start at 100 and drift slowly down to 60.5, despite the percentage gain being the same 10% gain or loss each time.

The trend is clearly downward. This is simply because the

loss is always calculated from a larger number than the gain. This would be the

same for any consistent repetitive gain/loss over time.

Of course the stock market doesn’t behave like this and the impacts are not played out like this. However, it is hopefully enough to give pause to also focus on avoiding losses in addition to making gains.

Of course the stock market doesn’t behave like this and the impacts are not played out like this. However, it is hopefully enough to give pause to also focus on avoiding losses in addition to making gains.