If the 2008/9 financial crisis was characterised as a credit-crunch, the 2020 COVID-19 crisis will probably be looked back on as a liquidity-crunch. Businesses were forced to shut down to help enforce social distancing, and as a result, in many cases, forgo any income for a period of time. It happened so quickly there was little time to organise a smooth landing for all parts of the economy, so many bills still had to be paid despite the lack of income. Investors would have seen unscheduled updates from the businesses they hold, stating their liquidity position, giving detailed breakdowns of borrowings, cash in the bank - all to reassure investors that they would survive the shut-down if it only lasted for x number of weeks/months.

I'm certainly better acquainted now with the notes in the accounts giving details on borrowings, restrictions and covenants attached to them, and when those debts need to be repaid. Many investors are cautious with regard to debt, the virus brought home exactly why. The spectre of insolvency became suddenly very real.

Insolvency is one of those words that I thought I understood - but only because I've never had to use it or think about it. There are a few bits of vocab that I have always confused, and as it turned out, researching and unpicking these provided much of the clarification I was after. I enjoy a good rummage on the internet for sources of information - in this case it was the legislation documents themselves. So apologies in advance to anyone legally literate for the rest of this post 😎.

Spoiler alert - it doesn't end well for shareholders.

Bankruptcy ≠ Insolvency

If a person owes money that they cannot repay, then they can be declared bankrupt. The individual or their creditors can apply to a court to become bankrupt and a legal process is then put in place to manage payment of debts, which can include formally agreeing to not repay the debt. The Government's Insolvency Service guide to bankruptcy is available here.

A company typically might have 3 different types of debt,

- bonds or credit notes which are sold on the debt markets

- a loan/ credit facility which is provided by a lender

- goods/ services on credit from a supplier

If a business cannot repay these debts (in the UK at least) they do not go bankrupt, but will become insolvent. Insolvency is a legal process, and as such there is legislation to follow - the Insolvency Act 1986.

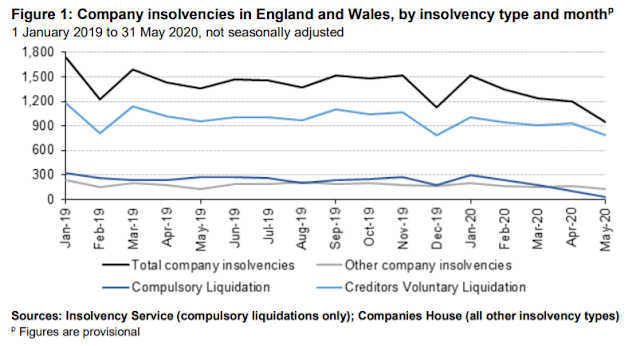

(Interestingly above the numbers of insolvencies reduce after COVID-19 appears - possibly due to Government support measures, and also to the courts shutting down.)

Insolvency has a specific definition:

A company may be wound up by the court if—

Source: Insolvency Act 1986 122(1)(f)

Even more specifically (and worryingly) the act (section 123(1)(a)) states that if a debt of at least £750 is unpaid 3 weeks after a written demand for it has been received, then the business may be regarded as insolvent. I'm sure many companies have payment terms that exceed this duration, but I'm not sure insolvency proceedings are the best way to get a hurry up on one's invoices, although it's likely to get people's attention...

There is also this juicy snippet in the Act:

A company is also deemed unable to pay its debts if it is proved to the satisfaction of the court that the value of the company’s assets is less than the amount of its liabilities, taking into account its contingent and prospective liabilities.

Source: Insolvency Act 1986 123(2)

No wonder then that companies have been rushing to prove adequate liquidity and demonstrate the strength of their balance sheets over the last few months.

Ok so we've established what insolvent means, what next?

If a company cannot pay it's debts it has a number of options open to it:

- Company voluntary arrangement (CVA), whereby the directors attempt to come to an agreement with creditors to accept less of the debt being repaid, but the company continues trading.

- Administration. This involves appointing an administrator to take control of the company with a view of hopefully rescuing the company, often through a sale of the business. Or if not then through the sale of assets and passing the resulting cash to creditors.

- Liquidation - sell the company's assets to pay off creditors, and close down the business.

Company Voluntary Arrangement (CVA)

The main problem with insolvency is the repayment of debt, so the CVA is a process for companies to ask creditors to reduce this debt, with the trade off being the increased probability that the business survives. For example a proposal may be to ask creditors to accept 80% of the outstanding borrowings, which will be repaid over 4 years, and in return the business will restructure in a certain way. Once the proposal is ready, creditors vote on the proposal and require creditors accounting for 75% of the value of the debt to agree. This has been a favourite tool of struggling UK retailers over the past few years, in particular with regard to property rents.

Administration

If a business goes into Administration an insolvency practitioner is appointed as administrator to take over management of the business from the directors. Their goal is not initially to shut down the business, but to rescue it. This is set out in the Insolvency Act:

Purpose of administration

3(1)The administrator of a company must perform his functions with the objective of—

(a)rescuing the company as a going concern, or

(b)achieving a better result for the company’s creditors as a whole than would be likely if the company were wound up (without first being in administration), or

(c)realising property in order to make a distribution to one or more secured or preferential creditors.

Source: Insolvency Act 1986 Schedule B1

Once an administrator has been appointed, creditors are barred from pursuing attempts to reclaim their loans unless given explicit permission by the courts. This provides the business with the time to work out a solution to it's indebtedness. This proposed solution is then presented to the creditors, who vote on the proposal, and if they can't form a majority the courts decide on an outcome.

Should the administrators find themselves unable to rescue the business, they may decide that they need to enter liquidation. This means that they will sell the companies' assets in order to raise the funds needed to pay creditors.

Liquidation

Liquidation simply means turning assets into cash, i.e. selling them. This is done to pay creditors, and if there is anything left over - to return this to shareholders. The process of liquidation can be started by the business, or can be forced upon it by the courts. Or of course the company administrator can move the business into liquidation if a rescue isn't possible.

What does this all mean for shareholders?

The good news is that shareholders have limited liability for the companies in which they invest - which means they are not liable for any debts incurred by a business. The bad news is that their investment may be lost.

It may not come to a complete wipeout, but shareholders are not first in the queue when it comes to payments from an insolvent business. First come those who have secured lending, then the fees of the administrators, then employee wages and pension contributions, then creditors with unsecured lending, floating charge holders, interest on debts, company share schemes, preferential shares....and then ordinary shareholders...no wonder there is little left to distribute to the average investor...

On that cheerful note, happy investing.